What is asthma?

Asthma is a chronic (long-term) condition where the lungs “overreact” to certain conditions or triggers. This leads to difficulty breathing. There are different reasons children develop asthma, but often the triggers cause inflammation in the lungs. While there is no cure for asthma, with proper management, children can play, exercise and lead normal healthy lives.

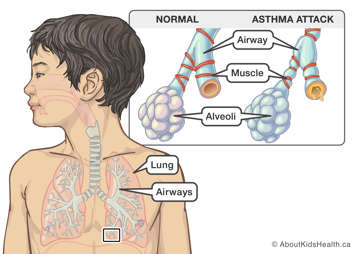

How asthma affects your child’s lungs

If your child has asthma, their airways (breathing passages) are extra sensitive and quick to react to certain conditions or triggers. When exposed to these triggers, the airways become inflamed, swollen and produce extra mucus, and the muscles around the airways tighten. When this happens, it blocks the flow of air into and out of the lungs. This makes it hard to breathe.

This click-through animation demonstrates what happens within the lungs during an asthma attack and how medications can help.

What are the signs and symptoms of asthma?

Asthma can affect different children in different ways. Common signs and symptoms include:

- coughing, especially at night or with exercise

- wheezing (high-pitched whistling sound when breathing in or out)

- chest tightness or heaviness

- feeling short of breath

Asthma symptoms are not always the same

Asthma symptoms can vary from child to child, even within the same family. Your child’s asthma may also look or feel different from one episode to the next. They may have different asthma symptoms triggered by different things.

Early warning signs

Asthma attacks (also called flare-ups or exacerbations) can happen suddenly, but often build up slowly over hours or days. Watching for early warning signs can help you identify if your child is having breathing problems. This can be especially helpful for younger children, who may not be able to tell you how they are feeling.

Early warning signs of asthma in your child may include:

- waking up at night due to coughing or difficulty breathing, even if only occurring once during the week

- being unable to keep up with other children, or taking frequent breaks, while playing or exercising

- having trouble catching their breath, or breathing faster than usual

- coughing

- vomiting from coughing

- needing to take reliever medicine more than two days during the week

If your child is experiencing early warning signs, follow the instructions on your child’s asthma action plan. This may include giving reliever (rescue) medicine more often and limiting physical activity until their symptoms are improved.

Asthma danger signs

Your child may show physical changes when their asthma symptoms are serious or when their condition gets worse. It is important that you learn how to spot these signs to know when to seek help from a health-care provider.

Asthma danger signs include:

- coughing or wheezing non-stop

- having difficulty feeding (babies) or having difficulty talking (children)

- feeling unusually sleepy or having trouble waking up

- “sucking in” of the skin around the neck or between/below the ribs while breathing

- appearing blue or grey around the mouth

- needing reliever medicine sooner than every four hours

If you see any of these danger signs, you need to act right away. Follow your child’s asthma action plan, continue giving reliever (rescue) medicine, and go to the nearest Emergency Department or call 911 immediately.

How do I know if my child is having trouble breathing?

How common is asthma?

Asthma is one of the most common chronic (long-term) illnesses in children. Up to 20% of children and adolescents in Canada have asthma.

What causes asthma?

There is no single cause of asthma. Many different factors, including genetic factors (passed on through families) and environmental factors, work together to make the airways more inflamed and sensitive in children with asthma.

Risk factors for asthma

There are some factors that may make your child more likely to have asthma. These include:

- having allergies and/or eczema

- having a family history of asthma, allergies and/or eczema

- being exposed to tobacco smoke before birth and/or during childhood

- having a respiratory infection called respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) during childhood

- being born early (premature) or with low birth weight

Remember, these are only risk factors. They make it more likely that your child may have asthma, but not every child with these risk factors has asthma. Children can also get asthma even without having these risk factors. For example, your child can still have asthma even if there is no history of allergies, eczema, or asthma in your family.

How is asthma diagnosed?

Early diagnosis and treatment of asthma and allergies are helpful to control asthma symptoms and prevent your child’s asthma from becoming worse.

To make a diagnosis of asthma, your child’s health-care provider will do the following:

- Ask you about your child’s current symptoms and past health, as well as the health of other family members, including asking about allergies and exposures to things that can affect breathing. This is called taking a medical and family history.

- Physically examine your child, including listening to your child’s breathing with a stethoscope.

- For children over the age of six or seven, they may order a test called spirometry or pulmonary function testing (PFT). During this test, your child will be asked to breathe out as fast and as long as they can through a special tube. The tube is connected to a machine that measures your child’s breathing.

It can sometimes be challenging for health-care providers to make a diagnosis of asthma in a young child, especially because that child may not be able to tell the provider how they are feeling. Asthma-like symptoms can also occur with other health problems. Your child’s health-care provider may need to see your child multiple times or give your child some medication before they can give a final diagnosis of asthma.

Allergy tests

Some children with asthma also have allergies. Being around things that your child is allergic to can make their asthma worse. Therefore, your child’s health-care provider may also order allergy testing. The most common type of allergy test is called a skin prick test. This is a quick test that can look for reactions to multiple allergens (allergic triggers). Results from this test take about 15 minutes.

You can read more about allergies and allergy testing in the Allergy Learning Hub.

How is asthma treated?

Asthma can be treated with many different medicines. Asthma medications do not cure asthma, but they can help control your child’s asthma symptoms, prevent future asthma attacks, and keep your child's asthma from getting worse. Most children need more than one medication to help control their asthma.

Developing an action plan for your child’s asthma

Your child’s asthma medicines are part of an asthma action plan that you will develop with your child’s health-care provider. The action plan tells you what to do if your child is well, having mild symptoms or having severe worsening. Remember that asthma symptoms may change over time. Have your child see their health-care provider regularly to monitor their asthma and adjust their action plan as needed.

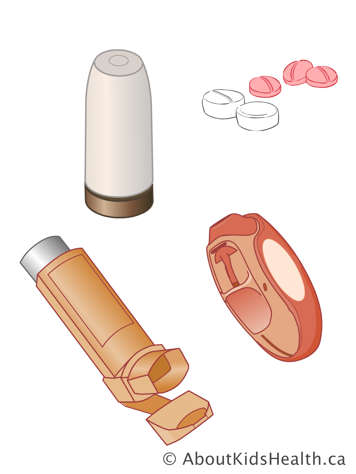

Types of asthma medicines

Asthma medicines can be broken down into different groups, including reliever/rescue medications, controller medications, and other medications. Some asthma medicines are inhaled (breathed in) and some are swallowed. Inhaled medicines have been shown to be very safe in children.

Reliever/rescue medicine

Reliever medicines are also called short-acting bronchodilators. "Broncho" refers to the airways, and "dilator" means expand, or open up. Short-acting bronchodilators provide quick relief for asthma symptoms during a flare-up. They are sometimes also used before exercise, to prevent worsening symptoms. Reliever medications work quickly, within just a few minutes, by relaxing the muscles around the airways. You will sometimes hear them called rescue medicines. Inhaled bronchodilators are available in two forms: puffers (metered-dose aerosol inhalers [MDIs]) or dry powder inhalers. A puffer can be used with a spacer in children and adults of all ages, while dry powder inhalers such as a Turbuhaler or a Diskus can be used without a spacer in some children over the age of eight.

Your child should always have their reliever/rescue medicine available in case they need to use it.

Examples of reliever medications include:

- salbutamol (Ventolin®, Airomir®)

- terbutaline (Bricanyl®)

Controller/preventer medicine

Controller medicines help to control the swelling (inflammation) of your child’s airways. They are used for long periods of time. Children with asthma will usually need to take a controller every day, even if they are feeling well, to reduce swelling and mucus in the airways and help prevent asthma attacks. Controller medicines should not be used as rescue medication during an asthma attack.

There are many different types of controller medications, including inhaled steroids (corticosteroids), inhaled long-acting bronchodilators (LABAs) and oral leukotriene receptor antagonists. Some children with asthma need multiple controller medicines to best manage their asthma symptoms.

Inhaled steroids

Corticosteroids are hormones that bodies naturally produce. Inhaled corticosteroids are very similar to these hormones. They are used daily to treat mild, moderate, and severe asthma. On average, inhaled steroids usually take from two and four weeks to start working.

These are some examples of inhaled steroids:

- beclomethasone (Qvar®)

- budesonide (Pulmicort®)

- ciclesonide (Alvesco®)

- fluticasone (Flovent®)

Long-acting bronchodilators (LABAs)

LABAs open up the muscles that surround the airways. Your child may take a LABA with an inhaled steroid, as they can help inhaled steroids to work better. They should not be used alone without inhaled steroids. Some examples of LABAs are:

- formoterol (Oxeze®)

- salmeterol (Serevent®)

Combination medicines

Combination medicines are a combination of inhaled steroids and LABAs. Combination medicines are a convenient way to take both medicines at the same time. They may give better asthma control. Some combination medicines are used for children of all ages and others are used only in children 12 years of age or older.

Some examples of combination medicines are:

- fluticasone + salmeterol (Advair®)

- budesonide + formoterol (Symbicort®)

- mometasone + fomoterol (Zenhale®)

Leukotriene receptor antagonists

Leukotriene receptor antagonists are pills that are taken daily. They help to prevent swelling and constriction of the airways. These may be used on their own, or together with inhaled steroids.

An example of a leukotriene-receptor antagonist is:

- montelukast (Singulair®)

Oral steroids

Oral steroids are used for severe asthma attacks to help reduce inflammation and swelling of the airways. Oral steroids come in pill or liquid form.

Examples of oral steroids include:

If your child’s health-care provider has prescribed oral steroids, make sure your child takes the full course of this medication. This will help stop your child’s asthma from getting worse. The course of steroids may last anywhere from two to five days. There are usually no serious side effects if your child takes oral steroids for this length of time.

Biologics

Biologic medicines target specific cells in the immune system that have been found to trigger severe asthma symptoms. These medications may be considered if your child’s asthma symptoms have not been effectively managed by other types or combinations of controller medicines. Biologic medications are given through a small needle under the skin (subcutaneous injection).

There are many factors that go into making the decision to start biologics. Your child’s health-care provider will discuss these with you in detail if biologic medication is being considered for your child.

Side effects

All medicines have the potential to cause side effects. Please review the potential side effects of each medication with a pharmacist or health-care provider. If you are concerned about your child experiencing any side effects, talk to their health-care provider. Your child should not stop using their asthma medicines without talking to their health-care provider first.

Administering your child’s asthma medicines

It is important to learn the correct technique for administering your child’s asthma medication. The videos and articles linked below will teach you how to use a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) with a spacer, a Diskus inhaler and a Turbuhaler.

If you have any questions about your child’s medications, talk to a member of their health-care team.

Metered-dose inhaler (MDI) with spacer

- Video: How to take your puffer with a spacer and mask

- Video: How to take your puffer with a mouthpiece spacer

- Video: Puffer + mouthpiece spacer – making the wrong sound

- Article: Using an MDI with a spacer

Diskus inhaler

- Video: How to take the Diskus inhaler

- Article: Using a Diskus inhaler

Turbuhaler

- Video: How to use your Turbuhaler

- Article: Using a Turbuhaler

How can I control my child’s asthma?

There are two important things that you can do to help control your child’s asthma. The first is to make sure that your child is taking their medications as directed by their health-care provider. Many children with asthma need to take medication even when they are feeling well. The second way to help control your child’s asthma is to minimize exposure to triggers that can make their symptoms worse.

Asthma triggers

Asthma triggers are different for each person. You can work with your child’s primary health-care provider to help identify them.

The most common asthma triggers in children are infections caused by viruses such as colds and the flu. To avoid getting sick, your child should wash their hands frequently and avoid contact with others who are sick. It is highly recommended that your child receives a flu shot annually in addition to their routine vaccines. Other possible asthma triggers include:

- allergens such as dust mites, animals or pollens

- cigarette, cannabis or vape smoke

- irritants such as air pollution or strong scents

- changes of weather, cold air or humidity

- strong emotions such as stress or anxiety

You can read more about asthma triggers in Living with asthma.

Frequently asked questions

Will my child outgrow asthma?

Asthma may be a lifelong condition for some children. It is difficult to predict. Your child’s asthma may be controlled for periods of time and uncontrolled at others. Some children are not bothered by their asthma as they get older.

Is steroid medication dangerous for my child?

Inhaled corticosteroids are some of the best medications for controlling asthma. There have been no long-term effects associated with low doses. The risks with higher doses of inhaled steroids are always balanced with the risks of uncontrolled asthma. In most cases, the risks of asthma outweigh any potential risks with inhaled steroids. Always talk to your child’s health-care provider to discuss the pros and cons of any medication. Your child will have their growth monitored at each visit to ensure they are growing adequately on the dose they are prescribed.

Can my child benefit from moving to a different climate or city?

It is not clear whether moving to another environment would help your child. Children may develop more triggers in their new environment that may aggravate their asthma.

Should my child see an asthma specialist?

Your child’s primary care provider has been trained to care for people with asthma. If their health-care provider is having difficulty controlling your child's asthma or your child is having frequent emergency department visits or hospital admissions for asthma, you may wish to be referred to an asthma specialist.

Will an air cleaner help my child’s asthma?

A HEPA (high-efficiency particulate air) filter has been proven to be effective in decreasing pet dander. It is not as effective at filtering smaller particles such as dust and pollen.

How do I use a puffer to give asthma medicine to my child?

It is always recommended to use a spacer with your child’s inhaler (also called puffers) to ensure the medicine is delivered directly to the lungs. Puffers should always be used with a spacer, regardless of a person’s age.

My child does not like using their puffer. What can I do?

Giving puffers may upset a young child. This is natural. Try to make it fun for your child by singing, counting, watching a video or showing them how to use the puffer on yourself or a teddy bear. Your child will become more comfortable with puffers over time.

How do I know when my child’s puffer is empty?

All puffers have a certain number of doses in them. While some inhalers have dose counters, the best way to know when a puffer is empty is to keep track of the number of doses used. This can be done by using a dose counting sheet.

How often do I need to replace my child’s spacer?

Most spacers last about a year before you need to replace them. Ask your child’s health-care provider for a spacer prescription when it is time to replace your child’s spacer.

How do I clean my child’s spacer?

It is very important to wash the spacer regularly to clear any build-up of saliva and keep the spacer working properly.

Once a week, wash the spacer with soap and warm water by hand and let it air dry. If your child has a cold or virus, it should be cleaned more often to prevent the spread of infection.

Follow-up care

After an asthma attack, it is very important that you follow up with your child’s primary care provider within one week of a visit to the hospital, even if your child feels better. This is to ensure that they continue to improve and stay healthy.

References

“Asthma in Canada.” Government of Canada, 1 May 2018, https://health-infobase.canada.ca/datalab/asthma-blog.html.

“Fact Sheet: Asthma Medications.” The Canadian Lung Association, https://www.lung.ca/sites/default/files/AsthmaMedicationsEN.pdf.