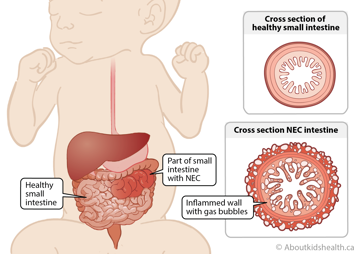

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a condition that typically affects the small or large bowels (intestines) of babies who are born prematurely or at a low birth weight (<1500g). NEC can also affect full-term infants who have underlying health problems, such as congenital heart disease or serious infections. NEC causes inflammation and infection of one or several parts of the bowels. In rare cases, it can affect the entire bowel.

Inflammation and infection in the bowels disrupt the blood supply and make the walls of the bowels become very weak. In severe cases, the walls become so weak that a hole forms (perforation). This hole allows bacteria and waste products, which are normally contained in the bowels, to leak into the abdomen and cause a dangerous infection.

NEC can be a life-threatening disease; however, most babies respond well to treatment. The bowel recovers and resumes normal function in most babies.

Signs and symptoms of NEC

NEC usually occurs a few days to weeks following birth. Signs and symptoms of NEC include:

- a red, swollen belly

- problems tolerating feeds

- bloody stools, including diarrhea containing blood

- vomit, containing bile

- irregular breathing

- low blood pressure

- high, low or unstable temperature

Diagnosing NEC can be difficult since its symptoms, such as not tolerating feeds, vomiting and altered bowel movements, are similar to signs of other less serious bowel conditions.

Causes and risk factors of NEC

While NEC can occur in any newborn baby, most cases are seen in premature babies. It is estimated that NEC affects approximately 5 per cent of infants weighing less than 1500 grams at birth.

It is not known exactly what causes NEC, but several different factors may contribute.

Prematurity

Babies born prematurely typically have underdeveloped immune systems and may not be able to fight infection on their own. The lower the birth weight, the more at risk a premature baby is of developing NEC. Babies born prematurely also have immature intestines that are more susceptible to infection and inflammation.

Formula feeding

Babies who are given breast milk have a lower chance of developing NEC.

Difficult delivery

In some difficult deliveries, not enough blood, oxygen and nutrients get to the bowels. The lack of oxygenated blood to the bowels can cause damage to the intestinal wall.

Bacteria

A premature baby’s immature immune system is not able to protect the bowels from an overgrowth of bacteria and germs. This can cause swelling and infection. Prolonged antibiotic treatment may also impact bacterial growth in the bowel, increasing the risk of developing NEC.

Diagnosis of NEC

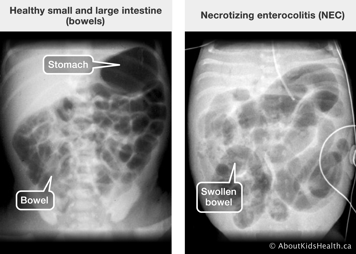

An abdominal X-ray is used to confirm a diagnosis of NEC and to determine how severe it is. The health-care team will look for swelling of the bowels, gas in the bowel walls (pneumatosis intestinalis) and free air in the belly (air outside of the bowels), which indicates that a hole has formed in the weak bowel. Repeat assessments of the baby's belly, as well as repeat X-rays, are used to closely monitor babies with NEC.

An ultrasound of the abdomen can also help confirm NEC by identifying parts of the bowel that have become thinner or if there is a change in blood flow to certain parts of the bowel.

NEC can significantly affect the absorption of nutrients into the body and the removal of waste products. In addition to imaging scans, a baby with suspected NEC will have blood tests to check for:

- evidence of infection (white blood cell count, blood culture, c-reactive protein)

- the balance of nutrients and chemicals in their blood

Treatment of NEC

When there is a concern that a baby may have NEC or when the diagnosis has been confirmed, the baby is not given any food into their stomach. This allows the bowel to rest and heal, which may take seven to 14 days. Liquids and nutrients (fat, sugar and salt) are given intravenously. A tube is placed into the stomach, either through the nose (nasogastric (NG)) or the mouth (orogastric (OG)) to remove any extra liquids or air. Babies may be given IV (intravenous) antibiotics to treat the infection. Some babies may also need support of their breathing and circulation. Once the bowel becomes healthy enough, feeds will slowly be restarted.

In most cases, this treatment is effective, and surgery will not be required, but up to one-third of babies may need surgery to remove the diseased bowel. In most instances where surgery is required, the diseased bowel is removed, and the healthy pieces are joined back together.

However, if there is disease in several areas of the bowel, the surgeon may pull the end of the healthy section through the abdomen, creating an opening in the skin called an ostomy. Stool or poop will pass through the ostomy into a bag. This allows the affected areas of the bowel to heal.

Once the bowel has healed, feeds will slowly be restarted. Babies will need a second surgery to close the stoma and reconnect the healthy section to the healed part of the bowel and remove the ostomy.

Outlook for babies with NEC

Most babies respond well to treatment and grow up without any intestinal or feeding problems. In rare cases, NEC may occur again.

Although uncommon, it is also possible that the development of scar tissue will cause the bowel to become narrow when it heals. This may block poop and gas from coming out and may require surgery to correct it. This narrowing is more common in babies who have had surgery to remove large sections of their bowel.

Resources

The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia: Necrotizing enterocolitis

References

Cuna, A., Morowitz, M.J., & Sampath, V. (2023). Early antibiotics and risk for necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants: A narrative review. Frontiers in Paediatrics, 11, 1112812. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2023.1112812

Samuels, N., van de Graaf, R.A., de Jonge, R.C.J., et al. (2017). Risk factors for necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates: A systematic review of prognostic studies. BMC Pediatrics, 17(105). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-017-0847-3

Children's Hospital Los Angeles. (2016). Necrotizing enterocolitis. Retrieved from: http://www.chla.org/necrotizing-enterocolitis (retrieved on January 14, 2025).