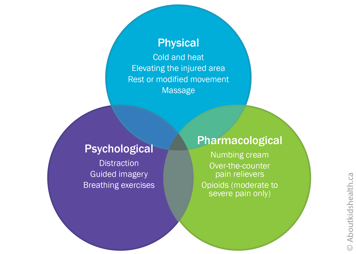

Most teens can manage their acute pain with a combination of psychological, physical and pharmacological (medicines) strategies, or methods. Together, these are termed the 3Ps of pain control. Like three legs of a stool, the 3Ps are complementary, or supportive, to one another.

Psychological strategies

Distraction

Distraction can be a particularly helpful psychological strategy when a teen is experiencing acute pain. Active distraction, such as doing an interesting activity, talking or playing a video game, is better than passive distraction such as watching TV.

Research shows that virtual reality (VR) technology can also help distract a teen during some acutely painful procedures like burn dressing changes. Relatively inexpensive options include mobile apps that your teen can use with simple VR glasses or headsets.

Guided imagery

To use guided imagery, ask your teen to imagine that they are in a calm, peaceful environment or to remember a pleasant experience from their past. Encourage your teen to describe what they see, as well as any smells, sounds or other sensations. Teens can also download online guided imagery scripts and follow them on their smartphone or other mobile device on their own during a painful procedure.

Breathing exercises

Breathing exercises help your teen slow down their breathing and become more relaxed. Encourage your teen to take a few slow deep breaths into their belly, breathing in through their nose and out through their mouth.

They can place their hands over their belly to check that it is rising with every in-breath and falling with every out-breath.

Physical strategies

Cold and heat

If your teen has any swelling or other signs of inflammation, it can be helpful to apply cold (such as a wrapped ice pack) to the area. This not only reduces signs of inflammation but can also help control pain. About 24 to 28 hours after an acute (sudden) injury, it can be helpful to apply heat (such as with a heating pad or a hot water bottle).

Be careful to avoid injury with heat and cold packs. Only apply them for short periods at a time (say, 10 minutes on/10 minutes off) and monitor the area closely. Your teen should be able to move the heat or cold pack away on their own or tell you if it is uncomfortable.

Elevating the injured area

If your child has pain and swelling after an acute injury, it can be helpful to elevate (raise) the painful body part to a level above their heart. Elevating a painful arm or leg, for instance on a pillow while your teen lies down, allows any excess fluid to drain. This in turn reduces pressure and pain in the injured area.

Resting or modifying movement

If your teen injures themselves, it is often a good idea to rest the injured area or at least modify (change) any essential movements for a time. This gives the injured area time to heal and protects it from further damage.

Be sure to talk to a health-care professional first because complete inactivity may sometimes increase swelling in the area and/or lead to loss of motion and muscle strength.

Massage

Massage can be a helpful form of physical therapy for acute pain due to cramps or sports injuries.

Pharmacological strategies (medications)

Pain medications can also help manage your teen's acute pain. These medications often come in different forms (for example liquid, tablets by mouth or through a needle). If your teen prefers one form of medication to another, have them play a key role in deciding which option is best for them.

Below is an outline of some common medications for acute pain. Because they treat different types of acute pain, some of them may be used together, if directed by your child's health-care team.

Always talk to a health-care professional before you use pain medications, especially if you are not sure which medication to use or which form of medication might work best for your teen. They can advise you if a pain medicine is safe and effective for your teen's type of pain.

Numbing creams

Numbing creams can be helpful for painful needle-related procedures such as vaccinations or blood tests. Apply the cream to the area where the needle will be injected 30 to 60 minutes before the procedure. Ask for directions from your pharmacist or health-care team.

Over-the-counter medications

It may also be helpful for your child to take acetaminophen or ibuprofen before or after a painful procedure. Taking these medications 30 to 40 minutes before a procedure is sometimes recommended.

These medications can often last four to six hours, so they can be particularly good for acute pain such as an earache or pain after an injury.

Opioid medications

Opioids are among the strongest pain relievers and are often used after surgery or other major acute painful procedures. If your older child is in moderate to severe acute pain, their health-care team may prescribe opioids such as morphine, oxycodone or hydromorphone, generally for short-term use.

| Opioids have risks and side effects, which can be serious. Always talk to your child's health-care provider for advice on taking, storing and disposing of opioids safely. |

Websites

Managing your child's pain from braces

https://1stfamilydental.com/reducing-braces-pain/

Managing your child's pain from sports injuries

http://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=tackling-kids-sports-injuries-1-4288

Preparing your child with cancer for painful procedures

http://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/children/preparing-your-child-medical-procedures

Page designed for children and youth to discuss their medication with their health-care provider

Five Questions to Ask About My Medicine

Videos

Pain management at SickKids (2 mins 49 secs)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_9_OQFo2APA

Reducing the pain of vaccination in children (Centre for Pediatric Pain Research) (2 mins 18 secs)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KgBwVSYqfps

Reducing the pain of vaccination in children (Dr. Taddio) (20 mins 52 secs)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=2&v=TGGDLhmqH8I

Learning how to manage pain from medical procedures (Stanford Children's Health) (12 mins 58 secs)

https://youtu.be/UbK9FFoAcvs

Content developed by Rebecca Pillai Riddell, PhD, CPsych, OUCH Lab, York University, Toronto, in collaboration with:

Lorraine Bird, MScN, CNS, Fiona Campbell, BSc, MD, FRCA, Bonnie Stevens, RN, PhD, FAAN, FCAHS, Anna Taddio, BScPhm, PhD

Hospital for Sick Children

References

Gold, J.I., Mahrer, N.E. (2017) Is Virtual Reality Ready for Prime Time in the Medical Space? A Randomized Control Trial of Pediatric Virtual Reality for Acute Procedural Pain Management. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsx129

Henderson, E.M., Eccleston, C. (2015). An online adolescent message board discussion about the internet: Use for pain Journal of Child Health Care 2015, Vol. 19(3), 412–418.

McMurtry, C.M., Chambers, C.T., McGrath, P.J., & Asp, E. (2010). When "don't worry" communicates fear: Children's perceptions of parental reassurance and distraction during a painful medical procedure. Pain, 150(1), 52-58.

Taddio, A., McMurtry, C.M., Shah, V., Pillai Riddell. R. et al. Reducing pain during vaccine injections: clinical practice guideline. CMAJ 2015. https://www.cmaj.ca/content/187/13/975

Uman, L.S., Birnie, K.A., Noel, M., Parker, J.A., Chambers, C.T., McGrath, P.J., Kisely, S.R. (2013) Psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD005179.pub3/full

von Baeyer, C.L. (2009). Children's self-report of pain intensity: what we know, where we are headed. Pain Research and Management, 14(1), 39-45.