What is a ventricular septal defect?

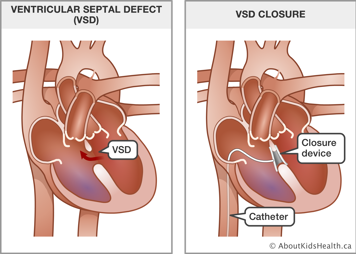

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is an opening or hole in the wall that separates the two lower chambers of the heart. This wall is called the ventricular septum. The hole causes oxygen-rich blood to leak from the left side of the heart to the right side. This causes extra work for the right side of the heart, since more blood than necessary is flowing through the right ventricle to the lungs.

The hole is usually closed with surgery. However, in certain situations, your child's cardiologist and surgeon may think it is best to close the hole with a special device. This procedure is done in the heart catheterization lab.

What is heart catheterization?

During heart catheterization, the doctor carefully puts a long, thin tube called a catheter into a vein or artery in your child's neck or groin. The groin is the area at the top of the leg. Then, the catheter is threaded through the vein or artery to your child's heart.

The doctor who does the procedure is a cardiologist, which means a doctor who works on the heart and blood vessels. This may not be your child's regular cardiologist.

To learn about heart catheterization, please see

Heart catheterization: Getting ready for the procedure.

There are small risks of complications from the procedure

Generally, heart catheterization is a fairly low-risk procedure, but it is not risk-free. The doctor will explain the risks of heart catheterization to you in more detail before you give your consent for the procedure. The most common risks with ventricular septal defect closure are:

The catheter may break through a blood vessel

There is a very small risk that the catheter may break through a blood vessel or the heart wall. To reduce this risk, we use a type of X-ray called fluoroscopy to see where the catheter is at all times.

Complications may occur with the closure device

The closure device may be placed in the wrong position. If this happens, the doctors can see it on an echocardiogram and will take the device out.

After the device has been opened, it may move out of position. If this happens, the cardiologist will try to take it out while the child is in the catheterization lab. If this is not possible, surgery will be arranged to take out the device and close the hole.

There is a small risk of heart rhythm problems

Sometimes the device can interfere with the heart's electrical system and cause problems with the heartbeat. This is called heart block. If this occurs, your child's cardiologist will discuss it with you in more detail.

For general information about the risks of heart catheterization, please see Heart catheterization: Getting ready for the procedure.

What does the closure device look like and how does it stay in place?

The closure device is made of metal and mesh material. It looks like a short tube with different-sized discs (circles) on either end. Before it is put in, the discs are folded so the device will fit in the catheter. When it is in the right place, one disc opens up as the device is moved out of the catheter. The tube portion plugs the hole and the other disc opens up on the opposite side of the hole.

What happens during the closure procedure

The procedure is performed while your child is under a general anaesthetic. This means that your child will be asleep during the procedure.

Not every VSD can be closed with heart catheterization. Therefore, we first need to measure the VSD to make sure it can be closed with a device in the catheterization lab.

When your child is asleep, we will do a test called a transesophageal echocardiogram. Echocardiogram means a heart ultrasound. Transesophageal means we do the ultrasound with a small probe that is placed in your child's esophagus, the tube that connects the mouth to the stomach. This test will measure the size of the hole and help place the closure device.

- If the test shows that the hole is too big to close with the device, we will wake up your child and send them to the recovery room. Your child's cardiologist will discuss the next steps with you and your child.

- If the hole is small enough and in the right position, we will go on with the catheterization.

During the catheterization, the doctor puts a catheter with a small deflated balloon on the tip through the blood vessel to the hole. The balloon is inflated to measure the size of the hole again. If the hole can be closed with the device, the doctor puts the closure device inside the catheter and places the device into the hole.

Once the device is in place, the doctor takes out the catheter and covers the cut on your child's leg with a bandage.

The procedure will take three to four hours

The procedure usually takes three to four hours. After the procedure, your child will go to the recovery room to wake up from the anaesthetic.

After the procedure

Most children will spend the night in hospital after the procedure. If your child needs to spend the night, they will be transferred to the inpatient unit from the recovery room. We will do an echocardiogram the next morning to check the placement of the device.

The cardiologist will let you know when your child can go home.

For information on what to do after your child goes home, please see Heart catheterization: Caring for your child after the procedure.

Coming back for a check-up

Your child will be given an appointment to see the cardiologist within three months after the procedure. At that time, tests will be done to make sure that the hole is properly closed.

Write the date and time of the appointment here:

Your child needs to take certain health precautions

Antibiotics to prevent infectious endocarditis

Your child will need antibiotics before and after dental treatments for six months after the procedure. These drugs help prevent a heart infection called infectious endocarditis. Your child's cardiologist will tell you if this is needed for a longer time.

Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) to prevent blood clots

Your child will need to take acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) for six months after the procedure. ASA will prevent small blood clots from forming around the device. The doctor or nurse will tell you how much ASA to give your child before your child goes home.

Write the instructions and dose here:

Stop giving the ASA and call your family doctor or paediatrician if:

- your child has a cold or fever

- your child is exposed to chickenpox

In general, you should give your child acetaminophen for fever and colds, as directed by your doctor. The doctor will tell you when you can start the ASA again.

If your child starts bruising easily, call your family doctor or paediatrician.